Don't Wait to Manage

the Weight

Angela Rollins, DVM, PhD,

DACVIM (Nutrition)

Several sources estimate about 50% of dogs and cats are overweight or obese.1 Pet obesity is associated with a number of ailments, including orthopedic disease, urinary bladder stones, endocrinopathies and dermatologic disorders.2,3 Excessive adipose tissue also increases anesthetic risk and hinders physical examinations and diagnostic testing.4 In fact, a lifetime study of Labrador Retrievers showed even modest over conditioning can reduce a dog’s lifespan by almost 2 years.5

Which dogs and cats are likely to become overweight? A large study of cat owners found obesity risk factors included a lack of owner awareness, being middle age (8-12 years), indoor housing and being spayed or neutered.6 Similarly in dogs, being middle age and neutered increases obesity risk.3 Studies evaluating the effects of spaying on obesity risk are mixed. Some studies show spayed females are at higher risk for obesity, while others show all female dogs, regardless of spay status, have high obesity rates.7-10 Understanding these obesity risk factors can help the veterinary team focus on prevention.

Prevention

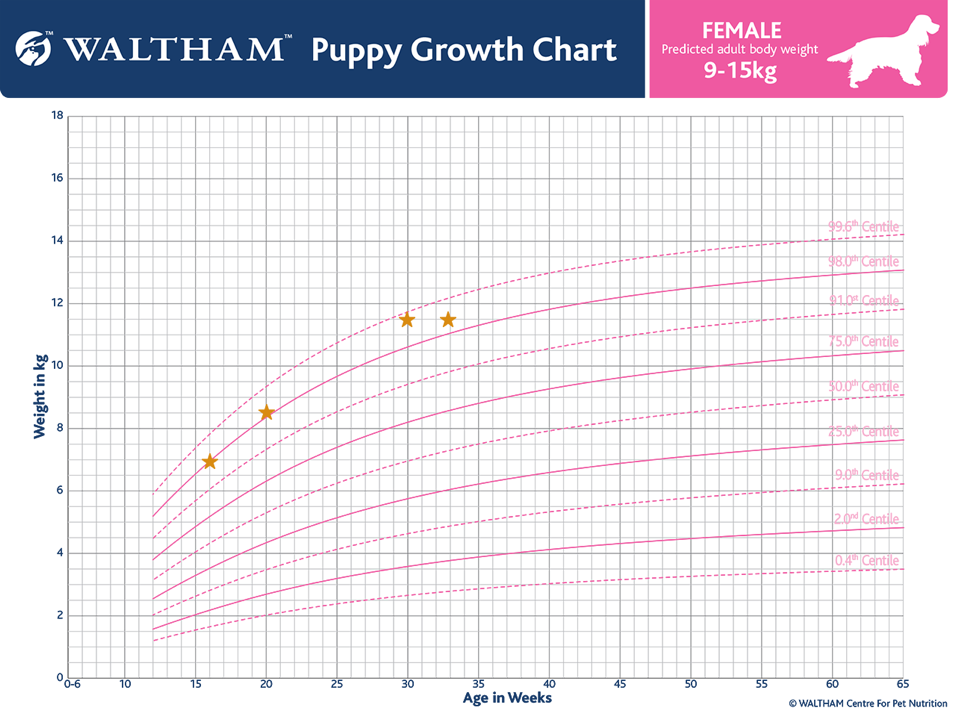

We’ve all heard the saying “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” This statement can be taken literally when it comes to managing pet obesity. The first step in preventing pet obesity is educating pet owners about ideal body condition. Overweight pets have become normalized, so owners may be unaware their pet is over conditioned. Conversations about maintaining a healthy weight should occur early in life with puppy and kitten visits. Puppy growth charts are a great tool for keeping puppies on track.

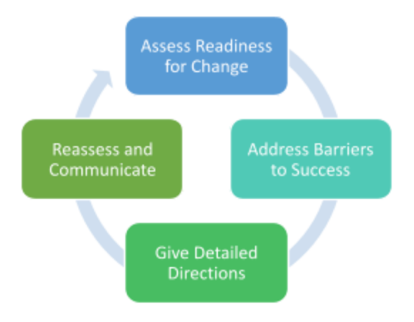

Spaying and neutering can contribute to obesity through a combination of increased food intake and reduced metabolism.11-13 Energy requirements of spayed and neutered dogs and cats are approximately 20%-30% less than intact pets, and this should be conveyed to owners at the time of surgery.13,14 Calculating new energy requirements for pet owners and moving to a food with lower energy density may reduce the risk of excessive weight gain.

How a pet is fed plays a critical role in preventing obesity.

Keeping our pets busy and making food a form of enrichment may reduce unwanted begging and destructive behaviors. There are many tools to encourage dogs and cats to work for their food. Treat dispensing toys, snuffle mats and puzzles are great ways to slow food intake while providing entertainment. The Indoor Pet Initiative website provides lots of tools and ideas for indoor cat enrichment. It is also important to prevent animals from stealing food from housemates. There are several feeder systems available that read microchips or collar tags to control access to food bowls between pets.

Treats can play an important role in training and bonding for pet owners. To prevent nutritional imbalances, treats should be limited to less than 10% of overall calorie intake. Low calorie fruits and vegetables can make great treats, or owners can use a balanced kibble if they need to give a lot of treats for training.

![chart_communication.png]() Communicating about obesity

Communicating about obesity

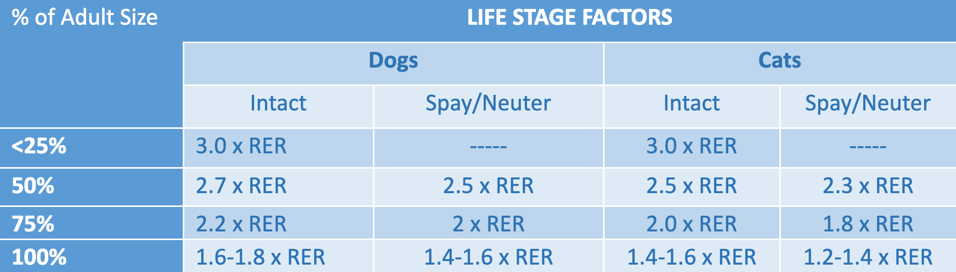

While obesity prevention is ideal, it isn’t always possible. A successful weight loss program needs to begin with commitment from the pet owner.15 Once a patient is identified as overweight, it’s important to convey the finding to the pet owner. For example, “I see Fluffy has gained weight since her last visit, and her body condition score places her in the overweight category.” At that point, you can determine if the pet owner is receptive to a weight loss plan by simply asking if they would like to continue the conversation: “Would you like to discuss a weight loss plan for Fluffy?” This opens the door to educate the owner about the health effects of obesity and discuss the steps needed to address it. Asking permission to continue the conversation helps assess an owner’s readiness for change while maintaining a good relationship with the client.

If a pet owner is receptive to starting a weight loss program, it is important to preemptively address barriers to success. For example, is the patient a cat with three other housemates? If so, a feeding system that separates pets with microchips or collars may be helpful. Do they provide lots of treats? Perhaps discuss using kibble for treats or give lower calorie alternatives. A good diet history form can provide valuable information to help address common issues surrounding weight loss plans.

Pet owners want veterinarians to give detailed advice in terms of nutrition. A weight loss plan should tell a pet owner what to feed, how much to feed and how to administer the food (frequency, bowl versus food puzzle, automated feeder, etc.).

![chart_weight.png]() Managing weight gain in growing animals

Managing weight gain in growing animals

What should you do if a puppy or kitten is already putting on the pounds? Instead of starting a strict weight loss program in a growing animal, it’s better to let them grow into their current weight. For example, if an 8-month old dog has a body condition score of 7/9 and weighs 15 kg, it’s best to try and hold their weight steady at 15 kg while they continue to grow, and eventually slim to a 5/9 as they mature. These are cases where a diet history is particularly important. Is the puppy fed appropriately but receiving lots of training treats? Is the kitten fed ad libitum with other household cats? Addressing issues in feeding management is key for preventing weight gain in growing animals.

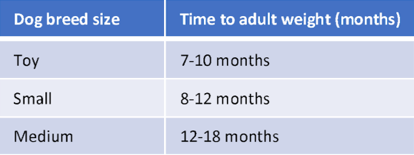

If a puppy or kitten is over conditioned, it is important to continue a diet designed for growth until they reach skeletal maturity. For cats this is typically about 12 months of age. Time to adult size will vary for dogs based on their breed size.

Most puppy and kitten foods are calorically dense, and there are limited options for growing animals that focus on obesity prevention. Utilizing a high-protein, fiber-enhanced diet that is calorically balanced for lower energy needs but still has nutrients for growth, such as Veterinary HPM® Spay & Neuter Junior Diets, may be a good option.

How much should a puppy or kitten eat?

There are several components to daily energy needs, but the biggest players are activity and maintaining homeostasis (aka resting energy requirements (RER)). RER typically accounts for 60%-80% of the total energy output. Estimations of RERs should be based on the current ideal body weight using the formula: RER = 70 (BWkg 0.75)

You can then calculate a patient’s daily energy requirements by multiplying RER by a life stage factor for growth. Daily energy needs = life stage factor x RER.

![img_maggiemay.jpg]() Case examples

Case examples

Maggie May is a 4-month-old, intact mixed breed puppy visiting your practice for the first time.

She weighs 15 pounds (6.8 kg) with a BCS of 5/9. Her owner is currently feeding a puppy food with 397 calories in a cup. She would like some guidance on how much she should feed Maggie per day. You calculate her RER based on 6.8 kg to be (6.8.75) x 70 = 295 calories. Using the puppy growth chart for females, 9-15 kg, you determine Maggie’s adult size should be about 13 kg, and she is currently is about 50% of her adult size. Therefore, you multiply 295 x 2.7 = 797 or about 2 cups of food per day.

Maggie returns four weeks later for her spay appointment and weighs 17.8 pounds (8 kg) with a BCS of 5/9. You mark her growth chart and find she is still on her appropriate growth curve. At 30 weeks of age, Maggie returns to your office to repair a small paw laceration. You notice her body condition has increased to 6/9 and she weighs 25.3 pounds (11 kg). After you repair her paw, you start a weight management discussion with her owner. Using her growth curve as a guide, you estimate Maggie May should weigh about 23 pounds (10.5 kg) and calculate her RER as 408 calories per day. Since she is about 75% of her adult weight and spayed, you choose a life stage factor of 2, equaling 816 calories per day. Her owner has continued feeding 2 cups of her puppy food daily, which equals 794 calories per day. Upon further questioning, you find Maggie also receives one dental chew daily (90 calories) and 10-15 training treats per day (totaling 50-75 calories).

Maggie is obsessed with eating, and her owner is reluctant to reduce her food amount.

Therefore, you switch Maggie to Virbac VETERINARY HPM® Spay & Neuter Large & Medium Junior Dog Food, with 348 calories per cup. When fed 2 cups per day as meals, this equals 696 calories. To keep her total calories around 800 and treats to less than 10% of calorie intake, you suggest that Maggie’s owner move to a smaller size dental treat or feed a treat every other day instead (45 calories per day). With a total of 750 calories from meals and dental treats, you suggest that her remaining 50 calories come from 1/8 cup of kibble (50/348 calories in a cup = about 1/8 cup) set aside for training reinforcement. Also, since Maggie is a busy puppy with lots of energy, you recommend placing her meals into treat dispensing toys or puzzles, rather than a traditional food bowl.

Maggie returns for a weight recheck with your veterinary nurse four weeks later and is maintaining at her previous weight of 25 pounds.

You are pleased that she is gradually approaching her ideal growth curve again. When she returns for her one-year puppy checkup, she weighs 28 pounds (12.6 kg), with a BCS of 5/9. Her RER is calculated to be 468 calories, and her life stage factor is 1.6 = 750 calories per day. Since this is very similar to her current calorie intake and she’s in ideal condition, you don’t recommend changing the calorie amount. However, you suggest transitioning to a maintenance diet for adults. Her owner is happy with her current diet, so she chooses to transition Virbac VETERINARY HPM® Spay & Neuter Large & Medium Adult Dog Food, which contains 313 calories per cup. 750/313 = 2 ¼ cups per day.

|

Communicating about obesity

Communicating about obesity Managing weight gain in growing animals

Managing weight gain in growing animals Case examples

Case examples